The owners of the East Greenwich gas holder now have a green light for demolition from the Department of the Environment and have submitted a planning application to Greenwich Council on the technicalities.

The intention of this blog post is to urge you to comment on the application – regardless of the situation. Follow this link to the planning application on the Council web site. The case officer is Elizabeth Jump – and you can just write to her or write to the Planning Department.

Also read the report included (under the Documents tab of the planning application) – most of it is very good and gives a lot of detail on the holder – one of two holders which were originally there – and the site itself. There are some mistakes, but, well, let’s not nit-pick too much.

We do need to be honest about this – the legal situation with planning is pretty well stitched up – and the same process has been used in other councils – like, for example, Tower Hamlets, where the holders at Poplar are now being demolished, despite an active campaign group.

So – what is going on? My guess is that the owners, Southern Gas Networks, are being panicked partly by Lewisham’s decision to locally list the Bell Green holders – and also because there is hardly a holder left now in London which doesn’t have a campaign group rooting for it. We need to understand their position – these large structures are expensive to maintain, and unless they are looked after will soon deteriorate dangerously – and without adequate security they are open to metal thieves, urban adventurers, kids climbing them for a dare, and who knows what else.

BUT there are lots and lots and lots of ideas out there from architects and designers on using old gasholder frames, and they are learning from past mistakes to do things better and cheaper. So what we need to do is to try and buy a bit of time – get them to put more security on the site – and give us some breathing space.

The other issue – which I know well – is how unhappy local people are with the level of development in East Greenwich – lots and lots and lots of tiny new flats and very little in the way of anything else. For many older residents (that’s anyone who has lived here more than 5 years!!) the Greenwich they knew is vanishing, upsettingly. We all need something to tie us to the place we live in, everywhere needs something about continuity as well as change. For a lot of people the holder is saying just that.

So write in – it is always important to make yourself known – and never go down without a fight.

Before 1800 most of Greenwich Marsh was let to commercial interests by corporate land owners. It had a management board – their earliest preserved minute books are from the 1630s – who employed a bailiff and staff.

Before 1800 most of Greenwich Marsh was let to commercial interests by corporate land owners. It had a management board – their earliest preserved minute books are from the 1630s – who employed a bailiff and staff.

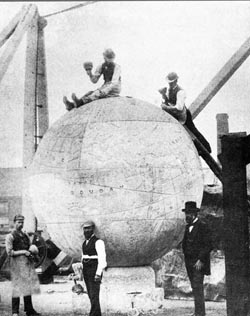

Thompson was the subject of an article by P. Barry in ‘Dockyard Economy and Naval Power’ who had visited Thompson’s works. He praised Thompson’s machinery as ‘practical ….expeditious and economical’ but also drew to the manufacture of wooden nutmegs in New England. His English readers may not have known that in America Connecticut is known the ‘Nutmeg State’ and that a wooden nutmeg refers to a native of that state whose intentions are dishonest.

Thompson was the subject of an article by P. Barry in ‘Dockyard Economy and Naval Power’ who had visited Thompson’s works. He praised Thompson’s machinery as ‘practical ….expeditious and economical’ but also drew to the manufacture of wooden nutmegs in New England. His English readers may not have known that in America Connecticut is known the ‘Nutmeg State’ and that a wooden nutmeg refers to a native of that state whose intentions are dishonest.

Mowlem’s Greenwich wharf was their ‘stone yard’. In the 1860s there are records of their ‘substantial buildings’. By 1869 maps show rails appear going to the river edge, and a slip with ‘mooring posts’ and a crane. ‘Cadet Place’ was called ‘Paddock Place’.

Mowlem’s Greenwich wharf was their ‘stone yard’. In the 1860s there are records of their ‘substantial buildings’. By 1869 maps show rails appear going to the river edge, and a slip with ‘mooring posts’ and a crane. ‘Cadet Place’ was called ‘Paddock Place’.